Recent years have seen rapid progress in the global push for greater transparency of beneficial ownership information – which is key for enabling sanctions compliance. But the positive developments have been twinned with significant setbacks. The result has been a uniquely dynamic information-gathering environment for corporate investigators, lawyers, and others, write S-RM's Toby Thomas and guest author Michael Barron.

First published in the December 2023 - January 2024 edition of The journal of Export Controls and Sanctions WorldECR and reproduced here with kind permission.

The ability to access beneficial ownership information plays a critical role in enabling sanctions compliance. But the preponderance of low transparency jurisdictions in multinational shareholding structures has meant that due diligence and investigation research into corporate ownership structures is often stymied by an offshore cul-desac, meaning it is not always possible to assert definitively whether corporate entities are controlled by designated individuals or their associates.

While the advent of beneficial ownership registers has had the effect of turning on spotlights across the globe, piercing the veil of offshore secrecy and publicly disclosing the identities of ultimate owners, the process is not without its problems – not least a widespread default to self-declaration, and limited repercussions for misrepresentation – but it nonetheless represents a critical step forward in the research environment for those seeking to understand sanctions exposure of potential counterparties. Here, we summarise recent changes to the availability of such information in key jurisdictions globally and provide an investigator’s perspective on the utility of ownership information made available to the public to date.

Background

The publication of the Panama Papers in 2016 made the role of offshore structures in occluding beneficial ownership front-page news, and revealed over 140 public officials using offshore entities to conceal the ownership of assets. The disclosure increased public pressure on the Financial Action Task Force (‘FATF’), the self-described global money laundering and terrorist financing watchdog, to expedite a solution; it had made gentle progress since first announcing this as a priority in 2003. In 2023, the fruits of a ratcheting up of transparency requirements on the 200 or so member states of the FATF and its regional affiliates are becoming clear. The gear-change towards corporate transparency has been accompanied by a counterresponse, driven by fears over privacy rights. A landmark EU court ruling in November 2022 resulted in many jurisdictions restricting public access to their beneficial ownership registries, creating a situation whereby countries previously perceived to be laggards when it comes to corporate transparency, at least according to indexes of perceived corruption – such as Nigeria and Mongolia – have outstripped more likely champions of the cause, including the Netherlands and Belgium.

FATF Guidance – ‘Significant reform?’

In March 2023, the FATF issued new guidance on implementation of its Recommendation 24 on the beneficial ownership of legal persons. This followed the revision, a year previously, of the text of the Recommendation itself. The revisions and new guidance place a greater emphasis on a country’s need to implement a central register of beneficial owners of all types of legal entities, to include foreign-owned entities and to exchange information with other jurisdictions; collectively, the revisions were welcomed by Transparency International as a ‘significant reform’.

The Recommendation is one of 40 that set out FATF’s international benchmarks for governments to combat money laundering and financing of terrorism. Governments are evaluated against these Recommendations on an eight year cycle. The evaluation reports are published, and a poor evaluation can lead to being placed on a FATF watchlist and impact a country’s ability to access finance at competitive rates. Recent additions to the FATF’s grey list include South Africa, Nigeria, and Turkey; it is perhaps no coincidence that they have also been among the fastest movers recently on implementing enhancements to the recording of beneficial ownership information.

EU AMENDMENTS

At the same time, the EU is debating further amendments to its anti-money laundering and counter financing of terrorism directive, the so-called 6th AML/CFT package. This includes further reforms to beneficial ownership reporting obligations under the 4th and 5th amendments. These amendments created an obligation on each EU Member State to introduce a central beneficial ownership register and allow public access to that register.

That right to public access was challenged at the EU’s Court of Justice by a group of business owners. The court ruled in November 2022 that public access to beneficial ownership information was not necessary for AML/CFT and was disproportionate. As a result, many EU Member States – including Austria, the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg – withdrew public access to their beneficial ownership registers. However, some Member States such as France and Denmark retained public access. They argue that there is a broader public benefit to access to this information.

Several EU jurisdictions have proved critical to understanding the flow of ownership by sanctioned individuals. Until the gradual opening up of EU beneficial ownership registries from 2019, Cyprus, Malta and Luxembourg – favoured investment destinations or conduits for Russian investors – were typically frustrating dead-ends for researchers involved in unpeeling layers of corporate ownership. (Whilst shareholding information was available, companies registered in these jurisdictions are often controlled by corporate entities registered in jurisdictions where such information is not available.) The opening of these, to differing degrees, led to major research breakthroughs from investigators, including the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project. However, subsequent to the November 2022 court judgment, the availability of such information in all three jurisdictions has been reversed.

UK AND CROWN DEPENDENCIES

The November 2022 EU court ruling has fuelled the debate on where the balance lies between the right to privacy and the right to information on who really owns companies. The impact of the ruling has been felt beyond the EU. Jurisdictions that were under pressure to grant public access to their registers have used the ruling to push back on that pressure.

In particular, some of the United Kingdom’s overseas territories and Crown Dependencies have stated that they need to consider the implications of the ruling before making their registers public – despite the ruling not applying to the UK or these jurisdictions. The UK’s overseas territories (such as the Cayman Islands and the British Virgin Islands) and Crown Dependencies (which include Jersey and the Isle of Man) are required under UK legislation to grant public access to their beneficial ownership registers by the end of 2023. A number of these jurisdictions are likely to fail to meet this deadline.

Meanwhile, the UK’s beneficial ownership register for companies, known as the Register of Persons of Significant Control (‘PSC’), remains free to access by anyone. The PSC register was the first publicly accessible beneficial ownership register anywhere in the world when it started operations in April 2016. Successive British governments have championed access to such information, not only for AML/CFT purposes but also for providing a public good. Companies House, which administers the PSC register, estimates that this information is worth several billion pounds to businesses every year. Nonetheless, there have been numerous challenges when it comes to verifying the information gathered by the UK. Changes which help deal with these are included in the Economic Crime and Corporate Transparency Act, which received royal assent in October 2023, and which promises to transform Companies House from a passive recipient of information into a more proactive custodian of reliable data.

AFRICA

The UK government has also promoted the creation of public beneficial ownership registers in other countries. It has funded research into creating a global norm for beneficial ownership transparency, funded the creation of registers and provided the model for others. For example, the UK government funded technical assistance for Ghana’s beneficial ownership register that became operational in 2021 and was the first publicly accessible beneficial ownership register in Africa. Nigeria’s register, which went live in June 2023, is modelled on the UK’s register including the use of the term ‘PSC’, rather than ‘beneficial ownership’. Like the UK equivalent, Nigeria’s register is free to access.

A number of other countries on the continent have also introduced beneficial ownership registers or are in the process of doing so. Kenya has amended its Company Act to require all companies to provide beneficial ownership information to the company registry. This information is not yet publicly accessible except in the case of public procurement. All respondents to public tenders must provide this information and, in theory, the beneficial owners of the winners of every contract are published. In practice, though, this is not always the case.

Other sub-Saharan African countries that have passed legislation in this area include Mauritius, Senegal, the Seychelles, South Africa and Zambia. In June 2023, South Africa issued the implementing regulations for amendments to its legislation that introduced an obligation on all companies to submit beneficial ownership information to the company register. At this stage, South Africa’s register will not be publicly accessible. All African countries have committed, at least on paper, to introducing public beneficial ownership registers through signature in 2018 of the African Union’s Nouakchott Declaration on anti-corruption – but the likelihood of most of them honouring this commitment in the short term is questionable.

MENA AND ASIA

In the Middle East and North Africa, the need to meet FATF requirements has driven progress in implementing beneficial ownership reforms. Jordan passed legislation in 2021 and enacted implementing regulations in late 2022. It is now in the process of collecting beneficial ownership on all legal entities in the kingdom and establishing a central register. The legislation has an enabling clause for future public access. At the time of implementation, Jordan was on FATF’s list of countries under increased monitoring, its so-called ‘grey list’. This and other reforms helped result in the country’s removal from the list in October 2023. In February 2023, Iraq started the process of collecting beneficial ownership information, in preparation for its first FATF evaluation in the second half of 2023. Egypt and Tunisia have also passed legislation but are yet to implement it. The UAE, a key conduit for investment activity including of designated individuals, passed legislation in 2020 requiring the disclosure of beneficial owners by 2021, but no public register has been made available.

In Asia, Indonesia was one of the first countries to introduce beneficial ownership legislation. A presidential decree in 2018 created an obligation on all companies to report their beneficial ownership information to the Ministry of Law, which administers the country’s corporate register. The register has limited public access. Mongolia introduced beneficial ownership reforms as part of its response to being grey listed by FATF, and was removed from the list in 2020. Initially, the register was not open to the public but in 2022, the country enacted right to information legislation which included specific provisions granting access to beneficial ownership information. The Philippines has also readily embraced a central beneficial ownership register, but its commitment to a public register is limited to voluntary disclosures by extractive companies. The region’s leading economies – China, Japan and India – are yet to institute public registers.

AMERICAS

The US has announced a significant ambition to transform its information-gathering environment, with major reforms due for implementation via the Corporate Transparency Act, which comes into force in 2024, and will result in some data being made publicly available but not beneficial ownership information. New York State may go a step further, with an act close to being signed into law which would make beneficial ownership information on companies public. In May 2023, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen conceded the merits of the perception that ‘the best place to hide and launder ill-gotten gains is actually the United States’, and indicated the incoming beneficial ownership register will make a serious dent in this.

Earlier in 2023, Canada introduced new legislation to implement a publicly available beneficial ownership registry of federally-incorporated companies. In Latin America, Ecuador has made the most progress towards implementation, with a public tenders register covering beneficial ownership. Although several jurisdictions have made commitments – with Brazil promising a non-public register, and Argentina and Chile publicly available registers, none of these have moved towards implementation yet.

Challenges

There are several key challenges when it comes to implementing and accessing beneficial ownership registries:

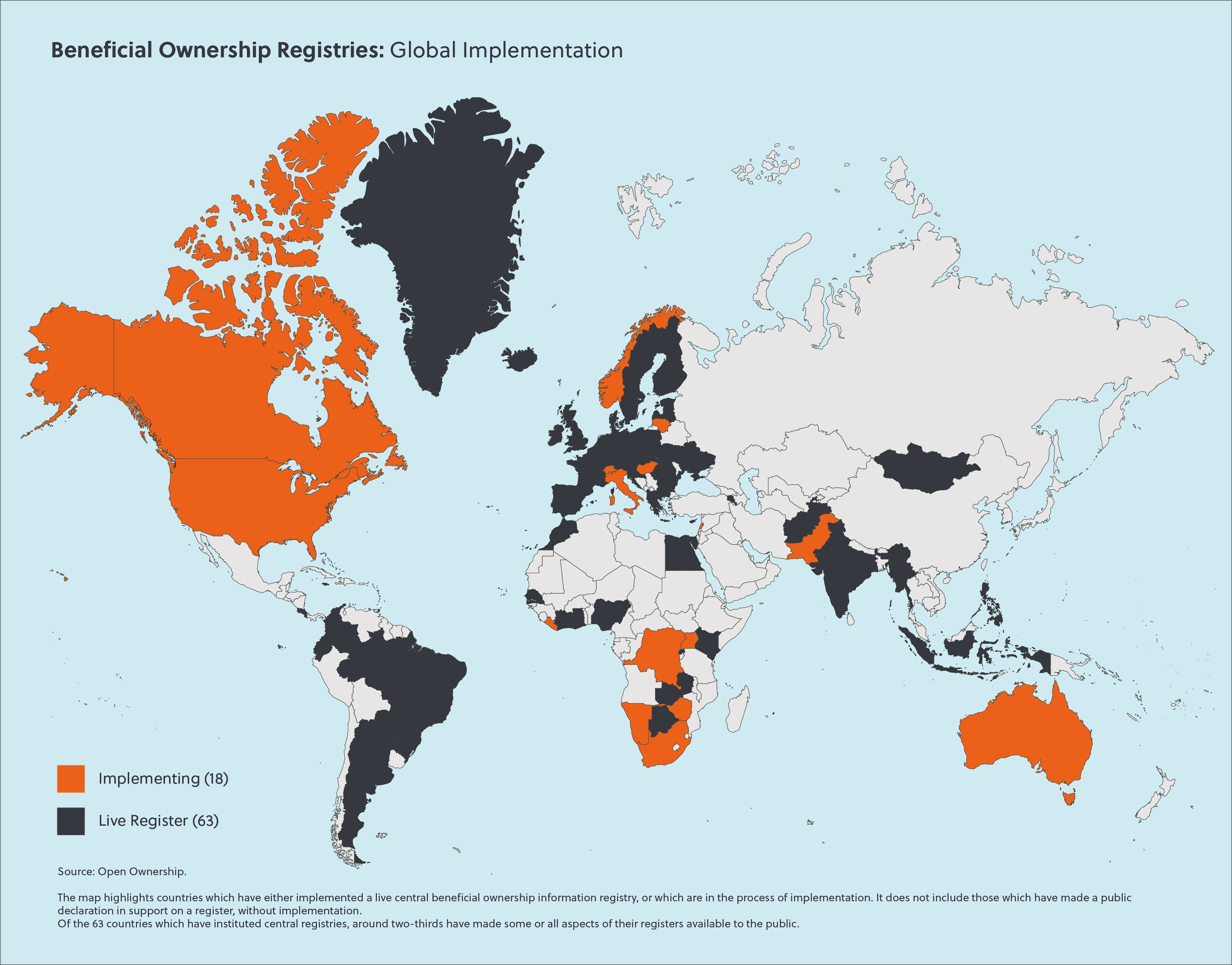

- Public or central? One of the main challenges facing every country creating a beneficial ownership register, whether public or not, is verifying the information supplied by reporting entities. Since the UK introduced its public beneficial ownership register in 2016, only 39 other countries have followed suit. A further 22 have implemented a central – but not publicly available – register. One hundred and ten countries have committed to introduce a public register, but it is highly questionable whether all or even most of these will proceed to full implementation. The absence of publicly available registers significantly reduces the effectiveness of due diligence.

- Verification. No country has yet completely met the verification challenge. Historically, many company registers have been passive recipients of self-reported information, which has allowed various approaches to fraud to flourish; a prominent legal critic has described UK Companies House as a ‘giant fraud robot’ as a result. Verification needs to happen at every stage, from initial data entry through to enforcement and penalties for noncompliance. Countries have put in a variety of measures to improve the reliability of information. These include requiring a senior company officer to provide assurance on the information reported, reporting any changes within a specified timeframe, an annual reconfirmation that the information remains accurate, a facility for users to report discrepancies and in some cases making it mandatory for certain users to report apparent errors. In the UK, banks, lawyers, accountants and some other professional advisors must by law report any discrepancies they become aware of between the PSC register and information they obtain from other sources. The UK’s Economic Crime and Corporate Transparency Act, which received royal assent in October 2023, promises to tackle the verification challenge head-on, and may inspire global imitation if it is effective.

- Completeness. Linked to verification is the challenge of incomplete data. Companies – especially those which may have something to hide – routinely flout requirements to complete data. For example, in early 2023, media reported that nearly half the companies in the UK’s Overseas Entities register which were required to declare their ownership had failed to do just that. Similarly, Kenya’s register provides for access to the beneficial ownership details of companies winning public contracts – but the information isn’t available on a consistent basis, either due to entry issues or administrative error.

- Corporate data aggregators. The drip-drip, and often relatively unheralded, nature of implementation has made it challenging for corporate data aggregators to stay fully up to date on the latest available data. Some premium vendors are sensitive to key changes, but it is not always feasible to enact API access at short notice. This re-emphasises the importance of regional experts running their own checks on a case-by-case basis of official records.

- Scope of application. The UK’s regime covers three key areas: companies; foreign owned land (the so-called Overseas Entities register); and trusts. Not all this data is equally available to the public, with the trusts ownership register being the most restrictive. Such an approach isn’t replicated globally, with many jurisdictions limiting implementation to sector specific areas: for instance, extractives companies, or in relation to those companies winning public tenders.

Overall, the dynamic nature of the beneficial ownership environment highlights one thing to those seeking to ensure compliance with sanctions requirements: creative research by regionally expert intelligence teams remains essential.

Toby Thomas is Director of Research, Corporate Intelligence, S-RM

Michael Barron is principal of Michael Barron Consulting Ltd (MBC), BO6.GLOBAL