INTANGIBLE AND IMPERMANENT: THE SOCIAL LICENCE TO OPERATE

Local communities have long been key stakeholders in the mining industry, but recognition of their place as core partners to both the opportunities and risks associated with mining operations has only recently emerged. In fact, in 2019 the World Economic Forum listed the Social Licence to Operate (SLO) as one of the key trends ‘shaping the future of the mining and metals industry’.[1] The SLO is an indicator of a community’s approval, or at least tolerance, of a mining operation. Initial adopters of the term, such as the World Bank, saw the SLO as the community-counterpart to a government mandated operational permit, except the SLO is not legally binding or contractually documented.[2]

Mining industry professionals have described the SLO as an ‘impermanent and intangible’ indicator of a community’s stance towards a mining project.[3] It is impermanent because the relationship between a mining operation and a community is subject to change, especially over the lifetime of a project. And it is intangible because the substance of an SLO is ultimately a feeling: rejection, acceptance, approval, trust. These characteristics result in high levels of uncertainty and unpredictability and make them particularly difficult to measure. Doing so requires careful, contextual analysis and, if possible, the quantification of the few available metrics that are meaningfully useful in such cases. Yet the implications of a damaged SLO are very much concrete, for communities and commercial operators alike.

An inexhaustive list of risks to communities and projects:

Between 1994 and 2014, of the 2,500 or so mining operations across the African continent, about 25% experienced ‘some form of social conflict’ within a 20 km radius.[4] A 2014 survey of 50 mining companies globally (nine in Africa) involved in community-related conflict revealed that these had incurred costs ranging from USD 10,000 – USD 750,000 a day and up to USD 20 million a week, all largely relating to operational delays as a result of ‘company-community conflict’.[5]

Range of operational costs resulting from company-community conflict:

USD 10,000 – USD 750,000 a day, and up to USD 20 million a week

Over the years, and as recently as 2019, we have witnessed several cases in which poor corporate governance has resulted in the loss of an SLO or subsequent tightening of the regulatory environment for mining companies. Importantly, while some of these cases were based on actual corporate governance failures, in others, simply the perception of a failure has reaped the same result and repercussions. This highlights the complex nature of SLO management.

Risk management and complex problem solving

Planning and executing community engagement strategies is the responsibility of corporate leaders, their operational teams, and dedicated in-house community relations and development (CRD) units. The role of risk managers (these could be in-house specialists, external consultants, or a combination) is not to set the strategy or oversee its execution. Rather, these individuals will work collaboratively across all levels of the business to help relevant stakeholders view their strategies and execution plans through a risk management lens. In so doing, the risk manager bridges some of the gaps that emerge as strategic vision translates into on-the-ground activity.

This is where the risks reside, and it is the role of risk managers to protect strategic goals by examining the range of human and systemic flaws that threaten them. To achieve this, these individuals are typically embedded as part of a team comprising corporate and community stakeholders. Involving community members in these consultations is key. In our experience, corporates that have taken active steps to exclude community members from such initiatives have been met with hostility and deprived themselves of important human intelligence networks which may have prevented subsequent security incidents.

With this in mind, risk managers can support SLO initiatives at two key stages:

1. Planning and preparation

Having a sound SLO initiative in place at the outset of a mining project can have a direct impact on its long-term success or failure. Studies have indicated that project suspension, curtailment or abandonment as a result of company-community conflict is most prevalent in the ‘feasibility and construction’ phases of a project.[6] An initiative, however, does not mean a “set-in-stone” plan. The most successful SLO initiatives we have seen and supported have emerged from ongoing learning and engagement, getting to know communities first-hand and remaining adaptable to changes in the operating environment. Such an approach has far greater long-term viability versus attempts to strictly follow pre-established academic frameworks.

"The most successful SLO initiatives we have seen and supported have emerged from ongoing learning and engagement."

Given the dynamic nature of this process, the risk manager can play a key role in mapping out possible futures. Scenario mapping entails creating and interrogating multiple potential future outcomes and the steps that lead up to them. The risk manager can help build sufficiently complex and detailed scenarios that explore a wide range of potential points of failure in the SLO initiative and open up project stakeholders to possibilities they may otherwise not have considered.

When facing highly changeable situations, remaining flexible and leaving room for unexpected outcomes is key to building resilience against future uncertainties. This is because, in complex systems, seemingly small incidents can have massive, rapid and unpredictable effects. Nevertheless, there are some tools at our disposal that can help with preparation. Doing a path dependence analysis, for example, can inform practical steps for avoiding unfavourable outcomes. Path dependence here refers to a series of small incidents that, cumulatively, have the effect of amplifying consequences and “locking-in” outcomes. Workshopping these paths, especially with a third-party consultant present, will bring to light potential biases or blind-spots that are more likely to lead an SLO initiative down an unfavourable path. Once the initiative is in motion, the CRD team will be empowered to identify these as they arise and make ‘small but prudent interventions’ to redirect the course of events accordingly.[7]

2. Complex investigations

In our experience, the risk manager, especially as an external consultant, is often brought in only at a point of failure, or in the build-up to what appears to be inevitable conflict between a company and the community. At this stage, their role is to answer two key questions: how did we get here, and how do we fix it? To achieve this, they will take an investigative approach, working back from the present to uncover root causes and contributing factors. By identifying root causes, the investigator will not only convey learnings for the future, but also identify those issues which, if addressed, may provide a systemic remedy to the current situation. This will be more effective than implementing solutions which tackle only the symptoms of a deeply embedded problem.

Historically, we have found that there is no “one-size-fits-all” approach to root cause analysis. Rather, the risk management consultant should examine the case in point and, drawing on their experience, determine the most appropriate framework for analysis based on this case’s unique properties. For example, in 2019, we conducted a root cause analysis for a client with operations in the SSA region. Our approach in this instance involved conducting witness interviews, reconstructing a timeline of events, reviewing internal documentation (to spot evidence of poor or misapplied procedures) and doing a barrier analysis (determining the presence, effectiveness and misapplication of mitigation and incident response measures and identifying misinterpretations of available intelligence).

"There is no “one-size-fits-all” approach to root cause analysis."

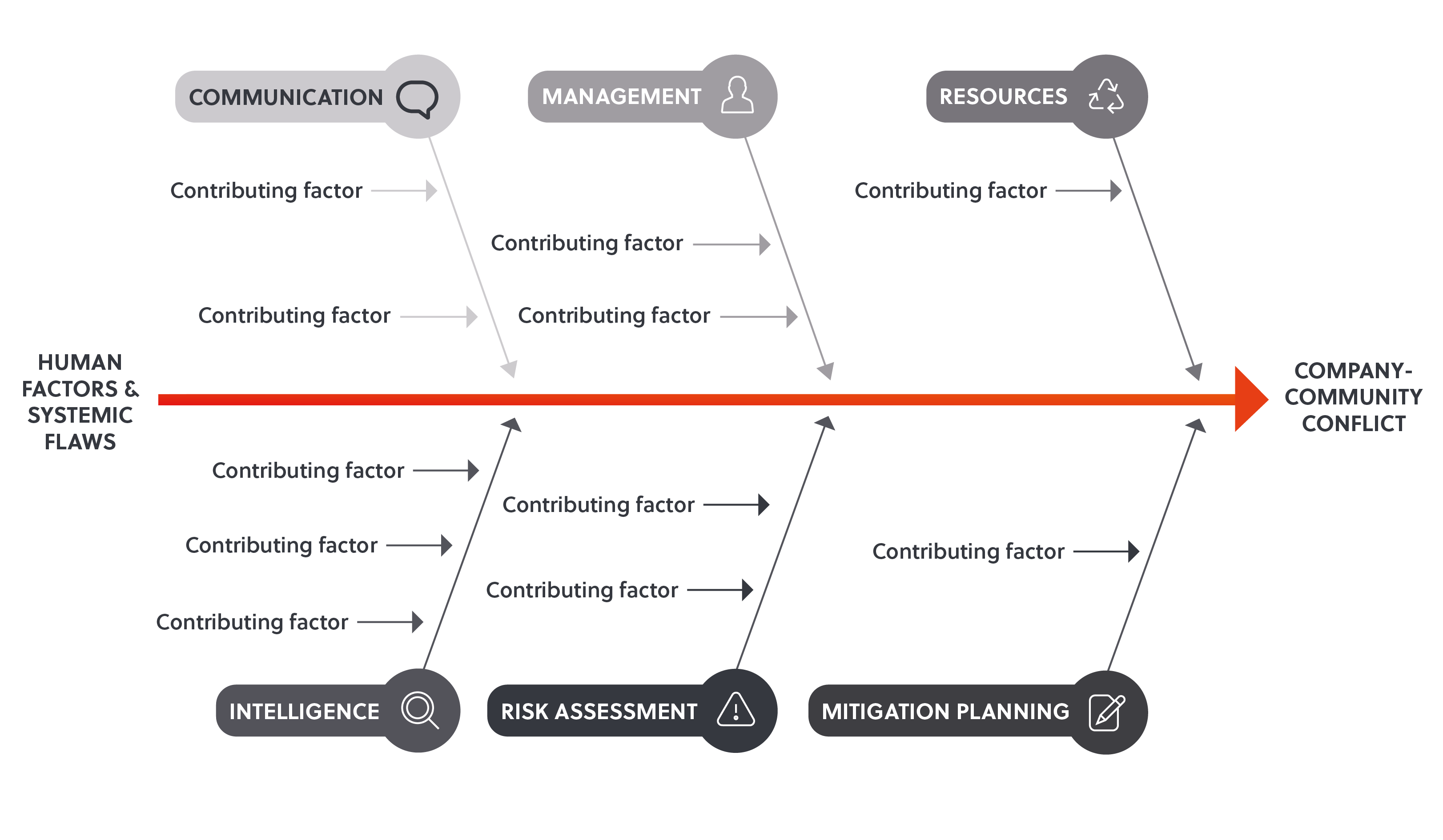

To summarise our findings, we used the Ishikawa Diagram (also known as a Fish-Bone Diagram because of its distinctive shape). While this is primarily a visualisation tool, mapping out cause and effect in this way often uncovers previously hidden links and relationships. The technique begins by identifying a “problem statement” and building out the “bones” of the diagram across a number of relevant categories, branching out the factors which contributed to their success or failure.

Sample Ishikawa Diagram:

Costs, accountability and the benefit of complex problem-solving

Studies on the cost implications of company-community conflict have traditionally focused on the physical threat to personnel and operational disruption, and the hidden costs of additional senior staff time required when an issue escalates into a crisis.[8] While these remain relevant, a growing human rights and environmental advocacy movement – as well as pressure groups from within corporations themselves – have seen the reputational costs of mismanaged community relations come to the fore. This socio-ethical shift is a welcome and probably overdue concern for the mining sector, and industry leaders are responding in kind. We have witnessed this first hand with a rising demand for specialist risk consulting services when it comes to community-relations planning and investigations focused on uncovering and resolving sources of tension and unrest.

By breaking down complex issues into their component parts, effective risk management will identify clear, actionable and focused solutions to such problems. The approaches outlined here have ongoing and inherent value – monetarily, ethically, and reputationally – for mining companies engaged in community-relations management and the maintenance of SLO initiatives.

References

[1] Maennling, N. & Toledano, P., 2019. Seven trends shaping the future of the mining and metals industry. [Online]

Available at: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/03/seven-trends-shaping-the-future-of-the-mining-and-metals-sector/

[2] International Finance Corporation, 2014. A strategic approach to early stakeholder engagement, Washington D.C.: The World Bank Group.

[3] Boutilier, R. G., 2014. Frequently asked questions about the social licence to operate. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal, 32(4), pp. 263-272.

[4] Steinberg, J., 2019. Mines, Communities, and States: The Local Politics of Natural Resource Extraction in Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[5] Franks, D. M. et al., 2014. Conflict translates environmental and social risk into business costs. PNAS, 111(21), pp. 7576-7581.

[6] Franks, D. M. et al., 2014. Conflict translates environmental and social risk into business costs. PNAS, 111(21), pp. 7576-7581.

[7] Liebowitz, S. J. & Margolis, S. E., 1999. Path Dependence. Encyclopedia of Law & Economics, pp. 981-998.

[8] Franks, D. M. et al., 2014. Conflict translates environmental and social risk into business costs. PNAS, 111(21), pp. 7576-7581.

Email Julian

Email Julian

.jpg)

@SRMInform

@SRMInform

S-RM

S-RM

hello@s-rminform.com

hello@s-rminform.com